Today we’d like to introduce you to Courtney Faye Taylor.

Courtney, we appreciate you taking the time to share your story with us today. Where does your story begin?

Most writers begin as readers, so I say my beginnings were defined by the literature I encountered early on. In middle school, I remember being assigned “Making a Fist” by Naomi Shihab Nye. I had to create a slideshow of images to go along with the words. I think that was the first time I was given the freedom to interpret a poem on my own. I was asked to participate in the creation of its meaning, and so I saw poetry as an ongoing conversation between the writer and the reader.

The church was another vital center of literature. I went to predominately white schools, so the Black churches I attended were, in many ways, cultural supplements to my education. They presented me with authors of my skin, my language, my experience. The children would recite poems by Maya Angelou for Black History Month, maybe some Langston Hughes for the Kwanzaa program. Black poets taught me that poetry is inextricable from history and community.

I imagine all these writers were with me when I took my first creative writing class and shared my poetry with others. When my words finally left the privacy of my own pages, they became something with stakes. They became an opportunity to shape the world, a responsibility to use language wisely. I’m always looking back to my beginning, to those writers, considering how I want my work to meet the world.

Would you say it’s been a smooth road, and if not what are some of the biggest challenges you’ve faced along the way?

Definitely not. I think the most consistent challenge is with rejection, not just dealing with it but finding the utility in it. Sometimes, a “no” is useful because it tells me I’m knocking on the wrong door. Sometimes, “no” tells me my work needs more time, which encourages me to revise, reimagine, and reconsider. So the challenge becomes flipping rejection into a guide rather than a definitive statement on my talent or trajectory.

But no matter how beneficial rejection can be, sometimes it’s just straight-up devastating. Part of what helps me push against that devastation is affirming my work. I remind myself of what I’ve accomplished and what I’m destined to accomplish. My favorite example of this uplifting self-talk comes from writer, Octavia Butler. Throughout her life, she wrote lists of affirmations.

There’s one list, in particular, that was found on the back of a spiral notebook, written in 1988. It had statements like, “I shall be a bestselling writer… each of my books will be on the bestseller lists of LAT, NYT, PW, WP, etc. My novels will go onto the above lists whether publishers push them hard or not. This is my life. I write bestselling novels… I will find a way to do this. So be it! See to it!”

Butler spoke her accolades, her hopes, her value into existence, and so it was true. I’m all about facing my dreams with that same unapologetic energy.

Alright, so let’s switch gears a bit and talk business. What should we know about your work?

I’m many things. I’m a senior writer at Hallmark where I write greeting cards, scripts, social media content, and more. I’m an educator who teaches creative writing workshops. Recently, I’ve become a visual artist after experimenting with collage. I’ve been an editor for literary magazines and book manuscripts. But I’m primarily a poet.

I’m putting the finishing touches on my first book of poetry, Concentrate. It’ll be published by Graywolf Press in November 2022. A poet I deeply admire, Rachel Eliza Griffiths, selected my book as the winner of the Cave Canem Prize, an award given to emerging Black poets. This prize was given to two U.S. Poet Laureates, Tracy K. Smith and Natasha Trethewey, at the beginning of their careers. It’s an absolute honor to be in this tradition.

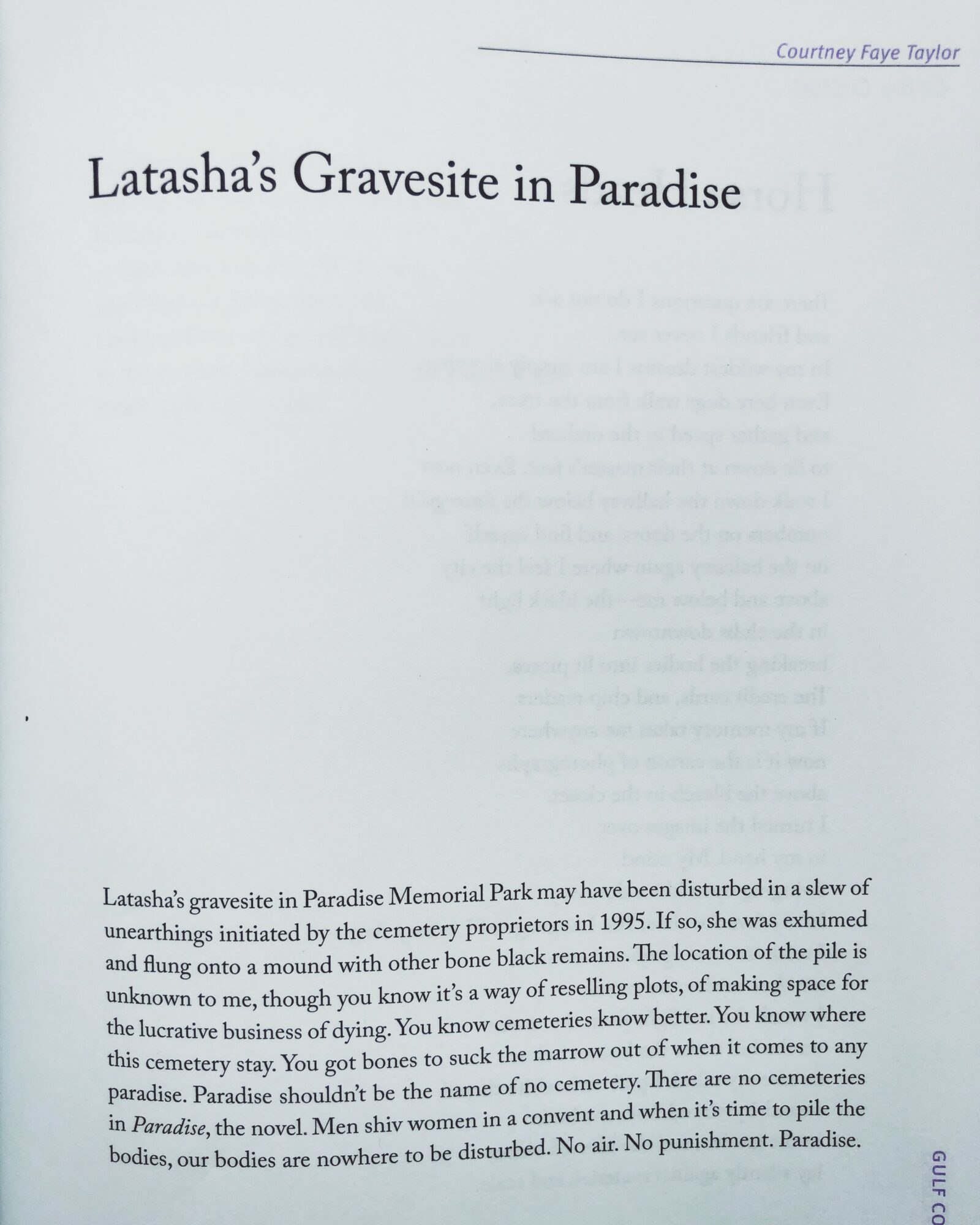

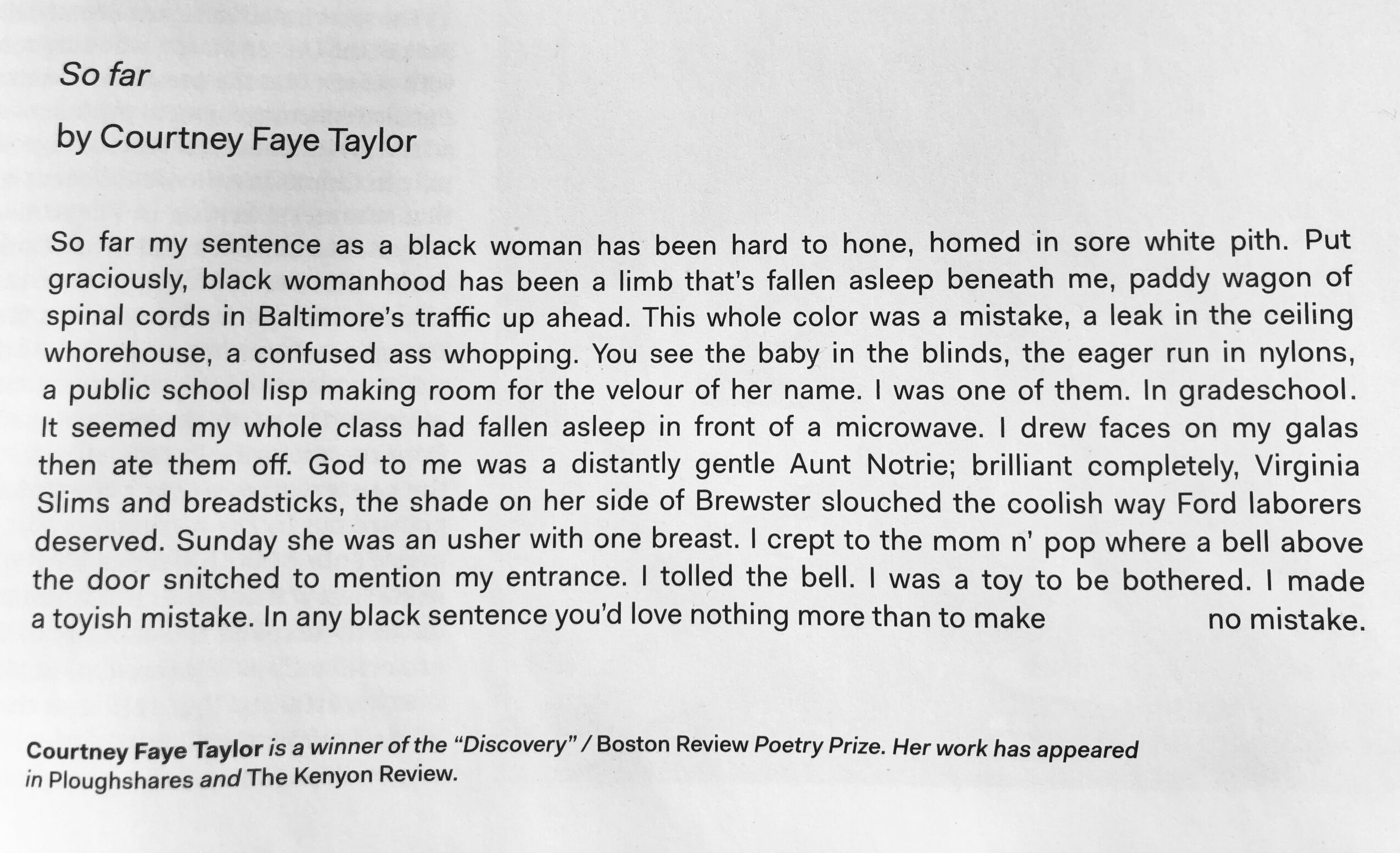

Concentrate is a meditation on the precariousness of Black girlhood, focusing on the story of Latasha Harlins, a fifteen-year-old Black girl killed by a Korean-American shop owner named Soon Ja Du in Los Angeles in 1991. Her murder, along with Rodney King’s beating, served as a catalyst for the 1992 Los Angeles Uprising. Through poems, photography, visual collages, dialogues, and micro-essays, Concentrate explores the tension between Black and Korean-American communities, specifically how white supremacy is the inventor and instigator of that tension. But the book also reflects on the unity that exists between these communities, and how solidarity is both a historic reality and a contemporary necessity for us.

Writing Concentrate taught me a lot. It showed me how writing is a collaboration between myself and the voice of my poems. To make each poem work, I had to be willing to let the poems have their say, their autonomy, their room to surprise me. I often hear writers say, “a poem teaches you how to write it,” and I agree; I definitely felt like the poems and I were collaborators. I could sense when I was making a poem do something it didn’t want to do. I got a certain feeling when a phrase or an image just wasn’t right. Likewise, I got a certain rush when the right expression or description made its way into the work. I enjoyed the frustrating and rewarding tug-of-war between me and the poems. It taught me how to trust my poetic voice.

Just as Concentrate was a conversation between me and my own writing, it was also a conversation between me and my history, me and my curiosity. It involved a lot of research; the research took me to South Central, Los Angeles, took me to the work of documentarians like Dai Sil Kim-Gibson, Christine Choy, and Elaine Kim, scholars like Brenda Stevenson, and playwrights like Anna Deavere Smith. Concentrate required my movement, my listening, and my understanding. I hope it does the same for its readers.

What makes you happy?

I’m most happy when I’m in the sunroom of my apartment. It’s a big deal to have access to natural lighting, especially in a state that gets cold and gray in certain months—sunlight is directly correlated to joy for me.

The sunroom is my green space. Watering, rotating, repotting plants—the act of keeping something alive is doing wonders for me. The sunroom is my literary space, too. I write and read in there. It’s my thinking space, my breathing space, my care space. Considering how difficult these pandemic years have been, I’m just grateful to have space.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://courtneyfayetaylor.com/

- Instagram: @thecourtcase

- Twitter: @thecourtcase

Image Credits

Image Credits

Headshot: Lucas Carpenter (“Latasha’s gravesite in Paradise”): published in Gulf Coast Journal: Cave Canem Foundation, (“So far”): published in The New Republic